Timing, they say, is everything. In October 2003, a full half-century had passed since George Pal’s movie adaptation of H. G. Wells’ classic alien invasion novel The War of the Worlds opened in theaters around the country. Then, as in 2003, Mars was in opposition to the Earth—meaning that it was at its closest point to our planet as its long, irregular orbit would take it. But even then, back before the days of artificial satellites, deep space probes and Hubble telescopes, serious scientists believed that Mars, our nearest planetary neighbor, was an unlikely candidate to harbor life. Only in the public mind did such a thing seem possible, thanks to the mistranslation of Giovanni Schiaparelli’s statement in 1877 that the surface of Mars was crisscrossed with canali meaning grooves or channels, not canals. Its thin atmosphere, its barren deserts, its great distance from the Sun, and its extremes in temperature argued persuasively against the possibility that life could thrive there.

Thankfully, that did not stop pioneering filmmakers like Howard Hawks, George Pal and William Cameron Menzies from imagining that world as being inhabited, or that beings from Mars might be hostile toward us; might journey here across the vast millions of miles of naked space to lay claim to planet Earth.

I was seven in October 1953 and until that time I had little inkling that I would spend the rest of my life fixated and preoccupied by such things. It’s been a wonderful half-century for which I have no serious regrets. But a day, a week, a month after having seen The War of the Worlds, had you asked me, “Well, young man, what did you think of that movie?” I would probably have complained of the nightmares it had given me, of how I imagined it to be real, and how I’d detected with my keen, young eyes, all the telltale signs that the invaders were actually near at hand. I would probably have said that only I had been sensitive enough to the truth of it to have seen those signs and pieced together in my mind the fact that we would soon be under siege. I remember seeing after an especially turbulent thunderstorm, what I now suspect were only shards of tree bark lying on the ground. They looked very much like the piles of smoldering ash that vaguely resembled the three human beings who once bravely stood guard in the gully at the beginning of George Pal’s movie version of The War of the Worlds.

But a full five months before I’d even seen The War of the Worlds, I’d seen another alien invasion film, one that was perhaps even more insidious because the invaders had found a way to infiltrate the sanctity of the American home, to move about unseen, and to take away the sweetness and decency of ordinary folk by making them pawns in their evil plans of conquest. These invaders, too, were from Mars, but they were not ruddy, lumpy, diminutive and feeble, as had been the creatures in the George Pal movie—no, these invaders were giants, green and furry, with terrifyingly blank faces and hauntingly empty eyes. This other film, Invaders from Mars, although greatly limited by its budget, holds a special place in the hearts of many people of my generation, because it mirrored the anxieties of those times so thoroughly that few of us would ever forget it.

Once casually dismissed as just one among many low budget science fiction films of the 1950s, Invaders from Mars now enjoys a large cult following—and rightfully so—and is regarded by some psychologists and social historians as an indicator of the deeper apprehensions of its day: flying saucers, the Cold War and, most especially, the fear of Communist infiltration. As a fair indicator of that era, Frederick C. Durant, III, someone quite credible and well known to the space sciences community, was president of both the American Rocket Society and the International Astronomical Federation at the time, and was also employed by the CIA. In January of 1953, Durant acted as recording secretary to a secret CIA-sponsored commission headed by Dr. H. P. Robertson, a physicist from Cal Tech, to review UFO evidence and to render an informed scientific opinion as to whether these objects posed a genuine threat to the national security. Using seventy-five specially selected case studies of UFOs given to it by the U. S. Air Force’s Air Technical Intelligence Command (ATIC) based in Dayton, Ohio, the commission concluded that the evidence contained no clear indication of a security threat, but it did caution that the UFO scare was such that it could be exploited by the Soviet Union to mask a nuclear attack against the United States. The Robertson report remained secret until it was made available by Freedom of Information Act requests filed against the CIA in the late 1970s. If nothing more, the very existence and conclusions of the Robertson Commission, and the revelation of its CIA sponsorship, demonstrate the uncertain state of international politics during the early 1950s, and the strong connection that once existed between the fear of Communism and anxiety over UFOs. In the earliest days of the flying saucer scare, most Americans believed that UFOs were secret weapons of either the United States or of the Soviet Union. The disclosure of the commission’s existence further indicates that the U. S. government, which publicly dismissed UFO sightings as hoaxes, hallucinations, and the product of Cold War hysteria, at least at one point, took the subject more seriously than it was willing to admit.

Presented as if it were a dream, Invaders from Mars tells the story of twelve-year-old David MacLean (Jimmy Hunt) who witnesses the landing of a flying saucer in a sandpit behind his home. The saucer bores its way underground and David’s parents and other members of the community are systematically dragged below and taken over by the saucer’s occupants. The strange visitors are from Mars and they are highly intelligent beings with huge heads and atrophied bodies. They are so physically feeble, however, that they must live in protective bubbles and have thus bred a race of artificial humanoids to do their bidding. These blank-faced, bulbous-eyed minions are large, man-like creatures that lope about subterranean passageways beneath the sand.

Their mission on Earth is to sabotage a nearby secret government rocket project. David’s father, George MacLean (Leif Erickson), is an engineer for the atomic-powered rocket under development and is the first earthling to be taken over. Earmarked for assassination by the alien-controlled humans are chief scientist Dr. William Wilson (Robert Shayne) and other scientists and military personnel essential to the project’s success.

With both his parents eventually under Martian control, young David attempts to tell his story to the few remaining adults that he trusts, but none will believe him. In desperation he runs to the police station for help, but is horrified to discover that Police Chief Barrows (Bert Freed) has also been taken over.

The desk officer, Sgt. Finley (Walter Sande), seeing that the boy is distraught, calls in psychologist Patricia Blake (Helena Carter). Dr. Blake is not entirely convinced by David’s story, but when his parents arrive to take him home, their cool demeanor prompts the psychologist to make up a tale about the boy’s health. Claiming that he must be taken to a hospital for immediate observation, Dr. Blake whisks David off to see Dr. Stuart Kelston (Arthur Franz), an astronomer whom David often visited before the secret rocket project caused authorities to declare Kelston’s observatory off-limits.

Kelston accepts David’s story without reservation and further speculates that the Martians might fear that the experimental rocket could endanger their realm of survival. He hypothesizes that the Martians might dwell in huge space-borne mother ships and that they have bred a race of synthetic humans—mutants—to cater to their needs. Positioning the telescope to observe the area behind David’s home where the saucer landed, Kelston, Blake and David witness the zombified George MacLean pushing General Mayberry (William Forrest), the commanding officer at Coral Bluffs where the rocket is being tested, into the alien-infested sandpit. Kelston calls in the military and the army soon surrounds the pit, prepared to do battle with the unseen invaders below. Commanding the troops is Col. Fielding, played by Morris Ankrum. Ankrum was something of a fixture of these mid-century science fiction films and he invariably portrayed authority figures—senators, scientists and, most especially, military men. Assisting Fielding is his long-time aide, Sgt. Rinaldi (Max Wagner). In short order, Rinaldi is dragged below by the Martians while heroically seeking a way into their underground hideout; and later Dr. Blake and young David get sucked into the Martian nest as well.

Now an instrument of the invaders, Rinaldi interrogates Dr. Blake when she and David are brought aboard the ship by two towering mutants. Dr. Blake is rendered unconscious because of her unwillingness to cooperate and is placed on a table to be implanted with a tiny control device. Before the implantation can be completed, however, the soldiers above, using another of the control devices as a locator, find the hidden saucer. They rescue Blake, David and Rinaldi and plant explosives aboard the ship, intending to blow it up. As the timer counts down the seconds to detonation, the humans frantically flee the area. During the tense finale, the events of the story are replayed in a long montage, first in sequence, and then in reverse order, superimposed over David’s image as he runs for safety. Just as the explosives ignite, David awakens to find that it has all been just a terrible dream. Tucked safely back in bed by his parents, he is again awakened a few hours later by the landing of the flying saucer, signaling that the nightmare is about to become real.

For the release of Invaders from Mars in the United Kingdom, approximately eight minutes were added and the film’s ending was altered. The additional footage, filmed in early 1955 with a noticeably more mature Jimmy Hunt, expanded the scene in Kelston’s observatory and involved a discussion of several well-known real-life UFO incidents. These include the Lubbock Lights (seen in Texas in August, 1951 and discovered to be reflections of newly installed Mercury street lights off a flock of Plover) and the death of National Guard Captain Thomas F. Mantell, who died in an airplane crash over Fort Knox, Kentucky on January 7, 1948 while in pursuit of what he thought was a UFO (it turned out to be a Skyhook balloon caught in the wind currents of the upper atmosphere). The revised ending abandoned the “it’s all a dream” aspect of the story and showed David being tucked into bed by Kelston and Blake as they reassure him that his parents’ surgery to remove their control devices had gone well and that they’d be returning home soon.

The original story and much of the final screenplay was written by John Tucker Battle (1902-1962) who had written screenplays for films as diverse as Disney’s So Dear to My Heart (RKO-Radio Pictures, 1949) and The Frogmen (20th Century-Fox, 1951), and later wrote for the popular western TV series, Maverick (Warner Bros. Television, 1957-1962). Immediately after his involvement with Invaders from Mars, he worked on an early screen treatment for Walt Disney’s now-classic rendition of Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Buena Vista, 1954); a film that won Academy Awards for its art direction and special effects (edging out Warner Brothers’ Them for the 1954 Special Effects Oscar).

At the conclusion of Battle’s final script the saucer is destroyed, but the Martian Intelligence and two of the mutants escape to return to their own planet. It might well have been director William Cameron Menzies’ idea to turn the story into a dream in order to justify the stark appearance of the sets and to play into the concept of seeing the story unfold through the perspective of the young protagonist. It was also decided during filming to change the story’s ending by having the Martian Intelligence destroyed with its ship, and to have the story cycle start anew with David’s awakening to see the saucer land a second time. When Battle caught wind of these intended changes he was furious and had his name removed from the screenplay and the film’s credits. Although much of what Battle wrote remained intact, screenwriter Richard Blake and Menzies made the final alterations to the script. Blake had previously written The Devil is Driving for Columbia Pictures (1937) and ultimately received sole screen credit for the writing of Invaders from Mars.

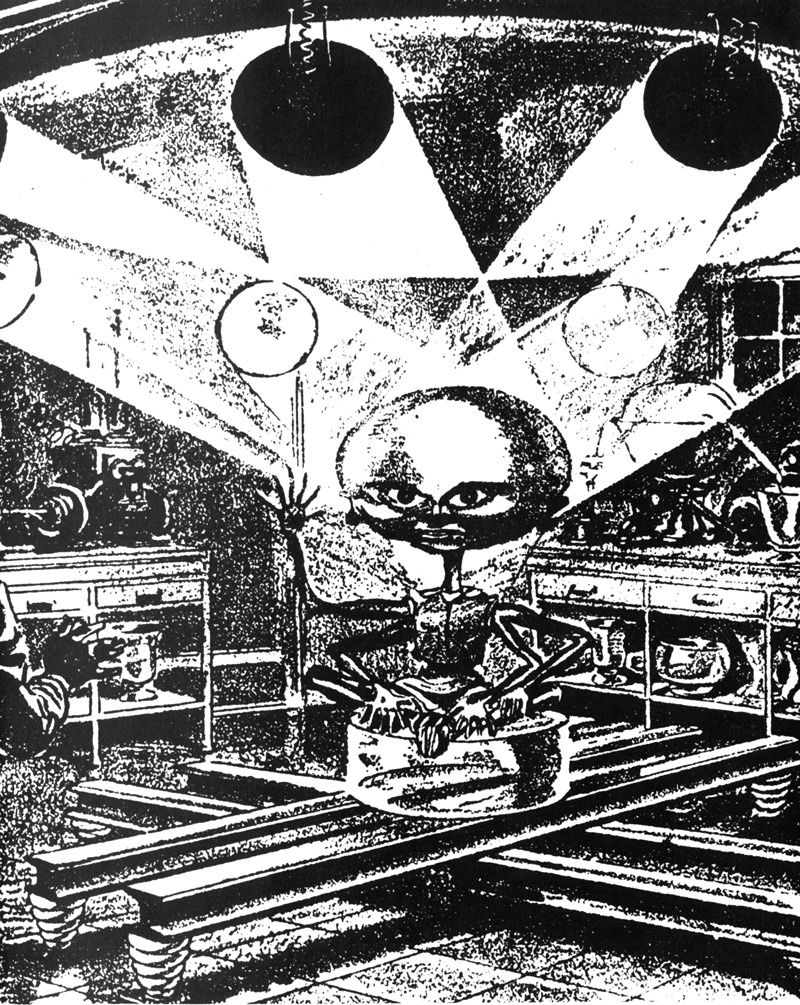

Menzies deviated from Battle’s descriptions of the Martian characters, too, feeling that a scientifically advanced civilization would use its technology rather than breed a race of artificial mole-like creatures to build underground tunnels with digging claws as Battle’s script suggests. Battle describes the mutants as being covered with coarse black fur and possessing a hairless, snout-like nose and beady, reflective eyes. In the completed film, the mutants manipulate their environment with a powerful disintegrating ray that melts and re-fuses the tunnel walls of their underworld labyrinth. In written form, the Martian Intelligence has an extremely brontocephalic cranium, deep-set eyes and a small, withered body that sits tailor-fashion on a circular cushion under a transparent plastic bell jar. Battle took as his inspiration an illustration from the June 1937 issue of Astounding Stories for the appearance of the Supreme Martian. The drawing, by Hans Wessolowski, accompanied the story, “Two Sane Men” by Oliver Saari. In Saari’s tale the grotesque entity was once a normal humana scientist named Edward Berkeley—monstrously transformed into a four-armed telepath. Again, in the final screen version, this character is somewhat streamlined.

As was necessary for such a low budget picture (reputed to have been produced for under a hundred and fifty thousand dollars) filming had to be done quickly and Menzies prepared a series of meticulous charcoal sketches intended to expedite the camera set-ups. Upon completing the sketches in early September 1952, Menzies passed them along to Richard Blake to help him with the descriptions for the final script. Sometime over the next three weeks the sketches mysteriously disappear, leaving Menzies at a terrible disadvantage. Under this tremendous handicap, Invaders from Mars began filming on September 25, 1952, and over the next four weeks live action shooting was conducted through ten-hour workdays on a six-day-a-week schedule. Even the post-production phase went swiftly, with the final cut of the film being completed on October 18th. Of all of Menzies’ films, and in spite of the unfortunate loss of his storyboards and the restrictive budget, Invaders from Mars is reputed to have been his personal favorite.

Invaders from Mars, produced independently by Edward L. Alperson, Sr., was released through 20th Century-Fox in May of 1953.Although its reviews were generally favorable and it quickly recovered its small investment, it was soon lost in the glut of similar movies. For those of an impressionable age, like myself, it became a source of nightmares. In addition to a fear of the unknown, the story worked quite effectively on the level of enemy infiltration. Few young Americans, I imagine, awakened the day after seeing the film without at least wondering if their parents were not really what they seemed. At the height of the Communist scare, the notion that seemingly ordinary people might be engaged in a secret conspiracy to subvert the workings of the everyday world, had suddenly found an outlet in the highly specialized medium of the American science fiction film. In that same year, Universal-International’s It Came from Outer Space, released a few weeks later in early June, struck that same jarring note (only in that case the aliens were not of hostile intent and could transform themselves to look like ordinary humans). The first time the theme of extraterrestrials subverting humans appeared in an American science fiction film was in Edgar Ulmer’s The Man from Planet X (United Artists, 1951), in which an alien exposes human subjects to a powerfully hypnotic light beam, thereby taking control of their minds. The idea soon after became a fixture of the SF films of the period, reaching its height in 1956 with Don Seigel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Allied Artists—this time, giant seedpods from outer space produce exact replicas of human beings, destroying the originals in the duplication process).

The film’s director, William Cameron Menzies (1896-1957), had studied illustration and painting with the likes of Harvey Dunn and Robert Henri (Robert Henry Cozad). Dunn, a noted illustrator and artist had, in turn, been a student of the renown Howard Pyle and set up a school in Leonia, New Jersey in the summer of 1913 which Menzies attended; Henri is best remembered for his paintings of urban realism and for being the ring-leader of the infamous “Eight”—the eight painters who broke with the national artists’ community to launch a controversial show in 1908 at the Macbeth Gallery in New York City. That show helped to change the direction of American art, moving it away from a bizarre derivation of French neoclassicism, toward the painting of more socially relevant subjects. Menzies studied with Henri at the Art Students League.

Menzies entered the motion picture industry while still in his teens, quickly working his way up to art director and defacto production designer and was soon regarded among the most notable talents in those areas of the film profession. Perhaps his best-known work in production design was for David O. Selznick’s Gone With the Wind (MGM, 1939), for which he received an honorary Academy Award. It was the first time the term “Production Designer” ever appeared on film, but it had not been his first Oscar, as he had previously won the award in 1927 for two films, Tempest and The Dove (both United Artists)—these were the first Academy Awards ever given for motion picture art direction. Menzies turned to film directing in the 1930s, but his output was relatively sparse. Many of his films were fantasies, and they include the seminal work of futurism, Things To Come (London Films, 1936). For the films on which he worked as director he also functioned as production designer, often without screen credit. Invaders from Mars is considered by historian Michael L. Stephens to be Menzies’ crowning achievement. He writes, “It is from this era [of the early 1950s] that Menzies made what many consider his masterpiece as a director/production designer, Invaders from Mars Such a low budget necessitates a certain approach in the production design and Menzies (with the assistance of [art director] Boris Leven) created a series of spare, largely white, shadowy sets which show the influence of German expression.”¹

Although he continued to work in motion pictures over the next few years, Menzies directed his last picture, The Maze (Allied Artists, 1953), soon after completing Invaders from Mars. One of the most eccentric movies of the 1950s, this 3-D effort is a curious union of horror and science fiction and deals with a two hundred-year old genetic anomaly—a man born a giant frog—who is secreted by his family in an ancient Scottish castle. Few youngsters of that time could forget the frog-creature’s climactic 3-D tumble from the upper window of the castle right into the audiences’ laps.

His last film assignment was that of associate producer for Michael Todd’s Academy Award-winning adaptation of Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days (United Artists, 1956). While Around the World in 80 Days was still in production, Menzies underwent surgery for cancer. For the last year of his life he was unable to speak. For someone so vividly remembered by his peers for his easy way with a good story, the inability to speak must have been especially frustrating for him. He died of a heart attack at his home in Beverly Hills on March 5, 1957, but clearly he has never left us. His haunting visual style will endure for as long as the medium of the motion picture continues to exist.

¹Stephens, Michael L., Art Directors in Cinema. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 1998.

Vincent di Fate is a science fiction/fantasy artist who’s work spans decades. He has been heralded as “one of the top illustrators of science fiction” by People and has several mantles full of Lifetime Achievement awards from the SFF community.